|

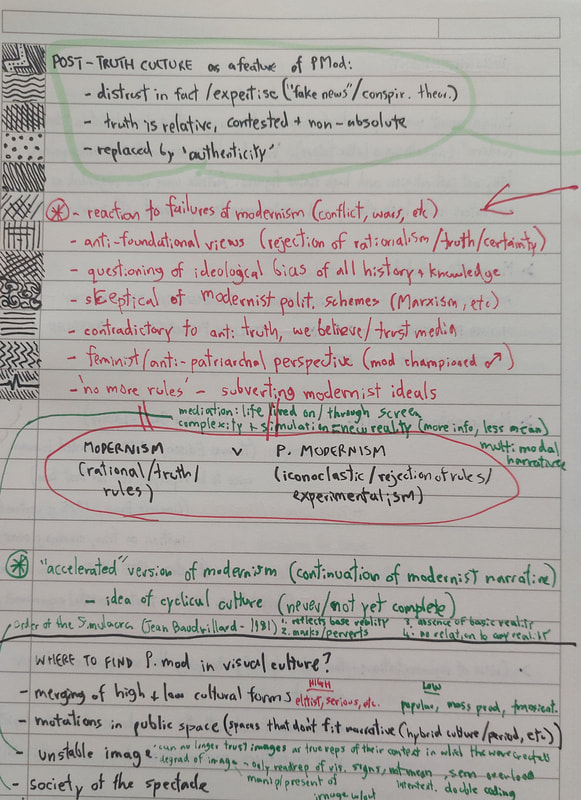

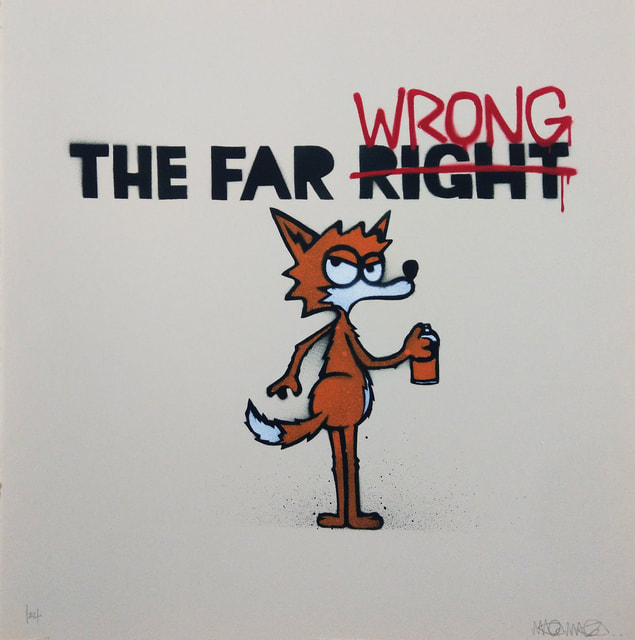

Modernism began mid-19th Century and lasted through to the late 1970s. It was a sustained period of industrial, scientific and artistic innovation which greatly affected cultural texts - rationalism was a relevant theme, as was the belief in a historical metanarrative. Postmodernism is a term that dates roughly from the 1980s to the present. It refers to the era beyond modernism - the time we are living in now, which is still under definitional debate. There are three different ways to view the concept of postmodernism:

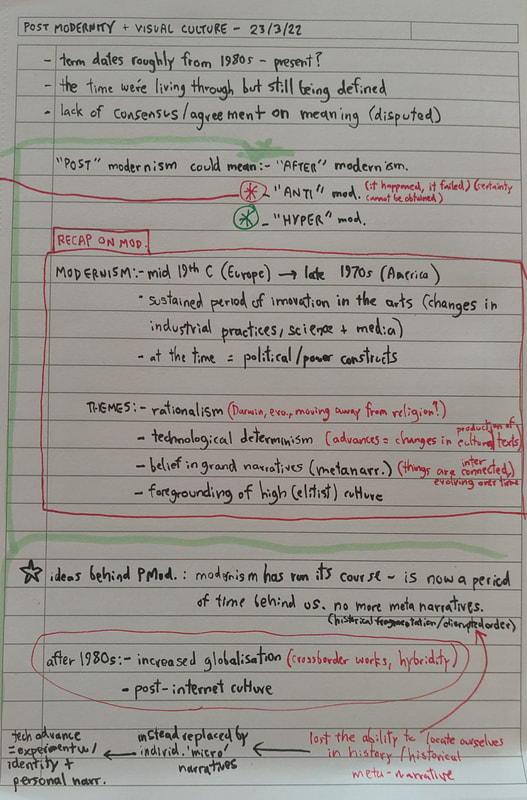

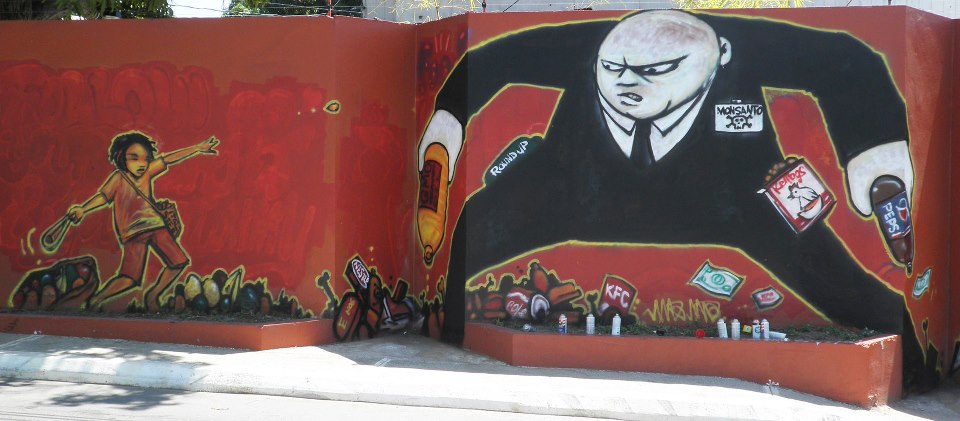

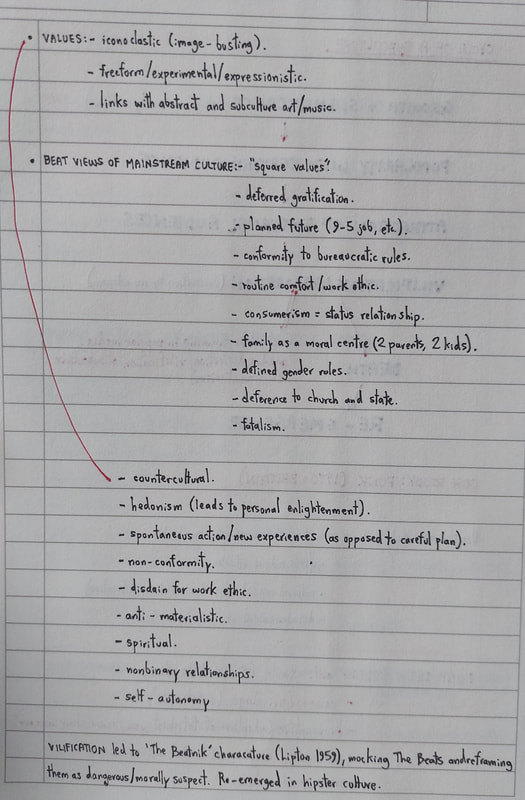

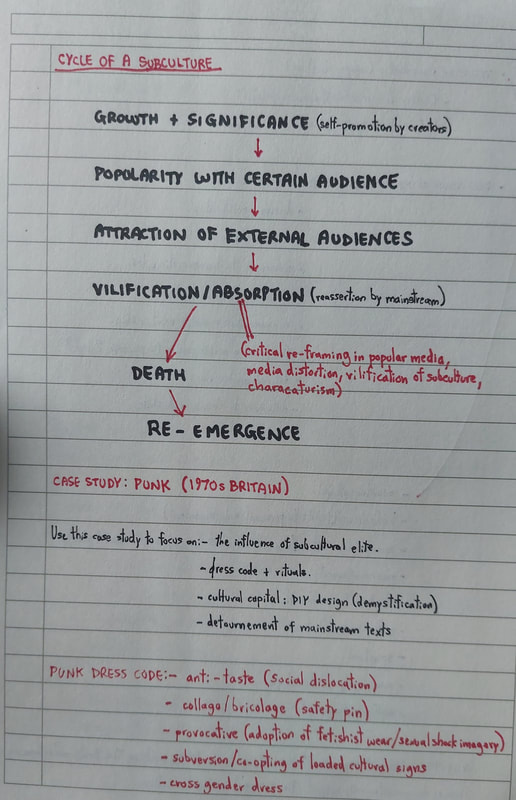

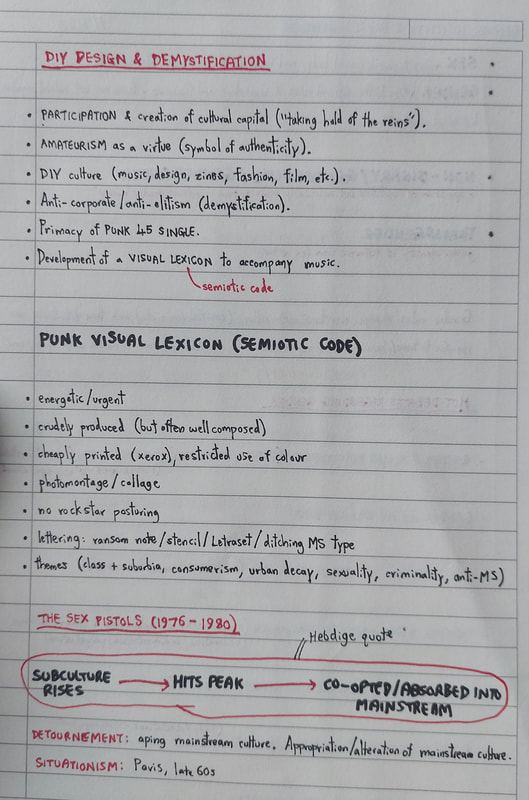

Postmodernism as Modernism's SuccessorProbably the simplest possible definition of postmodernism is literal and self-explanatory: the time period after modernism. After the 1980s, an increase in globalisation (cross-border work and hybridity) gave rise to what we can call post-internet culture. Technological advancements have led to experimentation with personal identity, and thus the creation of individual micronarratives - less and less are we able to place ourselves in that grand metanarrative championed by the modernist era. Another feature of postmodernism is the rise in post-truth culture. Unlike the widespread rationalist views of the modernist era, today's society has a certain distrust for fact and expertise. Seeing truth as contested and non-absolute instead, this culture has given rise to conspiracy theories and the advocation of authenticity. Postmodernism as an Anti-Modernism MovementAnother way to view postmodernism is as a reaction to the failures of modernism. In contrast to modernist rationalism and truth, postmodernism has iconoclastic values - it rejects and subverts these ideals, favouring experimentalism and anti-foundational views. We now freely question the ideological bias of known fact and history, sceptical of the modernist schemes society once followed. The concept of truth is rejected for the idea that certainty cannot be obtained, and we reject those rules modernism had previously placed upon us. Postmodernism as Hyper-ModernismThe idea behind hyper-modernism is that postmodernism is simply an accelerated version of modernism. In this sense, we are seeing a continuation of the modernist narrative; a belief that culture is cyclical, and never complete. Postmodernist Features?Postmodernist features in visual culture include:

GlossaryModernism: a sustained period of industrial, scientific and artistic innovation throughout mid 19th Century - late 1970s. Postmodernism: the current era which succeeded modernism - can be defined as after, anti or hyper modernism. Rationalism: the philosophical view that knowledge is acquired through factual reason. Post-Internet culture: a societal movement following the expansion of the Internet. Post-Truth culture: a societal movement challenging rationalist views. Metanarrative: a grand, overarching interpretation of history, interconnecting points in structural form. Micronarrative: a narrative personal to the individual, and unable to be placed within a metanarrative. *Order of simulacra: Jean Baudrillard's stage concept (1981): - stage 1: reflects base reality. - stage 2: masks/perverts reality. - stage 3: the absence of basic reality. - stage 4: no relation to any reality. Lecture Notes

0 Comments

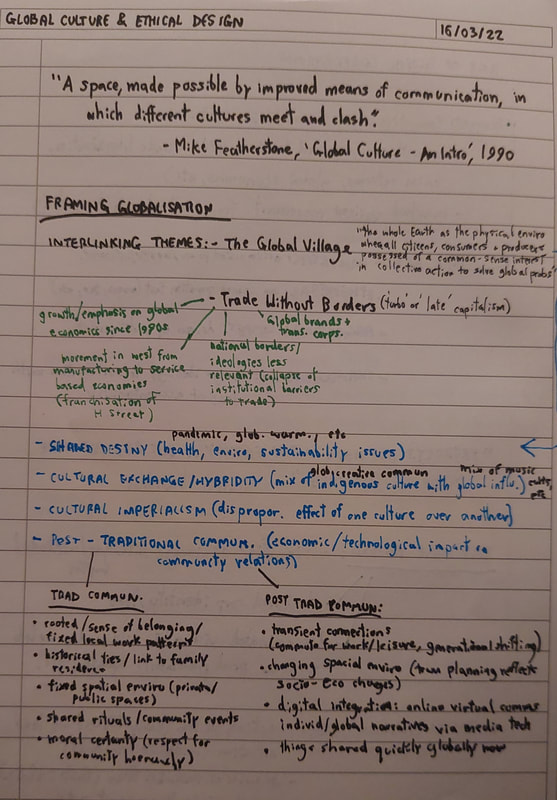

"A space, made possible by improved means of communication, in which different cultures meet and clash" |

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by 34SP.com